Before coming to Britain, even before embarking on our European journey, I would often sit and dream of treading through stone passageways, patrolling the length of rocky defences, and keeping watch from the tallest turrets on a windy night. Castles were raised by the ruling powers through the blood and sweat of their toiling subjects; impenetrable fortresses of carved stone blocks atop rocky crags, castles are truly an awesome sight to behold. They were, at many times, scenes of bloodshed: from sword clashing medieval battles to the assassination of nobles. They were once the seat of lords and kings, protecting, as well as dominating, the countryside. They have stood for hundreds of years and will hopefully continue to stand for centuries more (partially thanks to the National Trust).

When we finally entered the land famous for its castles, my dreams of exploring those magnificent fortresses came back to me and I wanted to visit as many as it would take to be sick of them. Needless to say I believe we met that goal; if I have to tour another bloody castle I may just leap off its lovely ramparts and drown myself in its quaint little moat. But looking back at our UK castle tour now I can re-appreciate the ‘magic’ behind their crumbling walls and their cold, empty rooms. We visited 16 castles in total on our Britain and Ireland tour, each one vastly different than the next and each with its own history, design, and legends!

Mow Cop

The very first ‘castle’ we came upon was with one of our HelpX hosts in Stoke-on-Trent, England. Phil took us out on a day trip up to the top of Mow Cop, a small village leading up a mountain. We got a bit lost along the way, thanks to a faulty GPS, and by the time we arrived at Mow Cop Castle it had started getting dark. The structure looked little more than a ruined sentry tower, sitting atop the summit of the mountain overlooking the entire county of Staffordshire below. As ancient and decrepit as it seemed, it was actually built recently in 1754 by a Randle Wilbraham as an elaborate summerhouse, designed to resemble a medieval fortress and round tower. The history behind this structure was perhaps a little pathetic compared to the castles our future tours brought us to, but at night, with strands of mist circling the hill like snakes, the Mow Cop summerhouse looked very much like an aged guard tower left behind by some ancient people. Since the late 20th century, Mow Cop is also known for its ‘Killer Mile’, a brutal, one-mile road race from the level railroad crossing on the western side of the hill, straight up to the tower.

Tamworth

Next on our list was Tamworth Castle, a fine example of Norman construction located next to the River Tame, in the town of Tamworth in Staffordshire, England. While we were staying in Stoke-on-Trent we chose to visit Tamworth simply because it was the closest castle we could find, and still being virgin castle seekers we would have been happy with anything. Luckily, Tamworth Castle turned out to be more than all right. We had a great time patrolling its high, shell wall over-looking the gardens and the river, exploring the old Norman Tower, and finishing with the armoury filled with gleaming medieval weapons and armour.

The original timber fort, on the hill where castle Tamworth now stands, was Mercian built in 913 by Queen Ethelfleda (daughter of Alfred the Great) to help repel the invasion of Danish Viking raiders. The Mercians were an Anglo-Saxon people who were the early settlers of the English Midlands, and Tamworth was where the Mercian’s capital city once stood, the seat of their high kings. When the Normans invaded in 1066, William the Conqueror gave the fort to one of his supporters, Robert De Marmion, who rebuilt and enlarged the castle into what you can see today.

Tamworth is considered to be one of the best preserved ‘motte-and-bailey’ castles, a design introduced to England and Wales by the Normans after their invasion. It was built on raised earthwork, a ‘motte’, accompanied by an enclosed courtyard, or ‘bailey’, surrounded by a protective ditch. Motte-and-bailey castles could be constructed extremely quickly with an unskilled workforce (usually slaves), only needed basic materials, and had excellent defensive capabilities despite being cheap to build. Tamworth Castle itself has a stone shell keep with a mighty three story tower known as the Norman Tower (the oldest part of the castle) and a herringbone stone causeway crossing the deep, dry moat.

The middle room of the Norman Tower is said to be haunted by a ghostly nun known as the ‘Black Lady of Tamworth’. According to legend, the Black Lady is the spirit of a nun named Editha, who founded her Convent in the 9th century. Long after her death, Robert de Marmion decided to expel the nuns from their convent for one reason or another (just to show how big of a douche-bag he is I suppose). The nuns prayed to their long dead mother Editha to help them, and so with swift justice on her heels, Editha rose from the grave and attacked Robert in his bed one night. She warned him that unless the nuns were restored to their convent, the Baron would meet an untimely death. Just before she vanished the spectre hit the Baron on the side with the point of her crosier, just to help get the point across. The wound from the crosier was so terrible that Marmion’s cries awoke the whole castle. His pain only ceased when he conceded and the nuns returned happily to their convent.

Newcastle

En route north to Edinburgh, we decided to spend a night in the quaint town of Newcastle-upon-Tyne before crossing the Scottish border. We enjoyed running around the city all night, exploring the many levels of cobblestone alleyways and bridges. We especially liked the Castle Keep and the Black Gate, all that remains of the original fortress of Newcastle, both within the centre of the city.

Use of the site of Newcastle for defensive purposes date back almost 2000 years from the time of Roman occupation, when it housed a fort and settlement called Pons Aelius. Pons Aelius got its name from the first bridge (or first ‘important’ bridge) to be built across the river Tyne to the Roman settlement. Pons Aelius naturally means “Aelius’ Bridge”, Aelius being the family name of Emperor Hadrian, who was responsible for, you guessed it, “Hadrian’s Wall”. In 1088, the prior mentioned Norman king, William the Conqueror, sent Robert Curthose, his eldest son, north to defend the country from the Scots. After Robert finished tangling with the Scots, he speedily moved to an area on the Tyne, the land where Pons Aelius once stood, and proceeded to build ‘New Castle’, erecting a motte-and-bailey wooden fortress from where the modern city of Newcastle gets its name. Nothing of the Norman fortress remains today, but in 1172 King Henry II built a tall, rectangular stone keep (looks a little bit like Lord Farquad’s castle from Shrek). Later, around 1250, a great, outer gateway to the castle was built and donned the ‘Black Gate’.

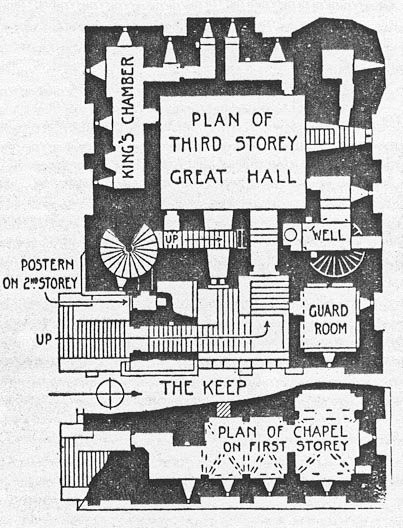

Very little remains of what was once a great castle, thanks to the Scottish who besieged the walls for three months straight in 1644. ‘The Keep’ is still in good condition, a roughly square building, measuring 81 feet tall. The entrance leads to the second floor and into the Great Hall, the largest room in the keep. It’s actually quite intimidating the way it towers over you, reminiscent of a grade school bully. The menacing sounding ‘Black Gate’ also has retained its looks, though covered with a bit of foliage. The gate acted as the first line of defence for the original castle; it consists of two towers with a passageway between them and was once accessed via a drawbridge across a moat.

Newcastle-upon-Tyne seems to be the Mecca for paranormal investigators as the city is alive with stories from countless ghost sightings. From an old lady named “Silky” chasing boys away from apple trees to a repenting Viking seen praying in the graveyard, the ghosts of Newcastle are a cast of diverse characters that seem to multiply every year. For a full list of Newcastle hauntings, check out the Paranormal Database for Newcastle.

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is a sprawling, grey-stone, cobble-road city. Built on seven hills, its landscape dominated by an extinct volcano called Arthur’s Seat. Strolling up on a slow incline, Ashleigh and I passed restaurants advertising their tasty haggis, souvenir shops selling far too many knock-off kilts, and marvellous stone-work buildings. The Royal Mile, in the old town, led up to a great fortress called Edinburgh Castle, which overlooked the city below from its position upon the aptly named Castle Rock. The entry fee was pricey, as it is with many of the more well-known tourist attractions, but it was a sacrifice we were willing to make.

Archeologists have established that Castle Rock and the surrounding area have been occupied by settlers since the late Bronze Age, with evidence of a hill fort on Castle Rock and some of the surrounding hills. The recorded history of Edinburgh Castle is long and arduous; The hill fort of Din Eidyn upon Castle Rock was first written to be owned in 600 AD by a King Mynyddog Mwynfawr and his tribe of Gododdins, who, after feasting and drinking for a year, decided to wage war against the Angles (due to sheer boredom), and were subsequently wiped out during a battle at Catterick, Yorkshire. The Gododdins in Din Eidyn were then invaded by the Angles and the site of was renamed to ‘Edinburgh’. The fort remained in Anglian hands along with the entire region of Lothian until they were forced to withdraw, due to several rebellions by the native peoples, and the area became a part of Scotland during the reign of King Indulf in 954. The Castle of Edinburgh that you see today was (mostly) built in 1130 by King David I who developed Edinburgh as a seat of royal power. Over subsequent years Edinburgh Castle was the site of many sieges, changing hands between the Scottish and the English at least four times over a 50 year period, and has been rebuilt, remade, and remodelled over the centuries. By 1999 Edinburgh Castle had become one of the top tourist destinations in Scotland, and now has more than 1 million visits per year.

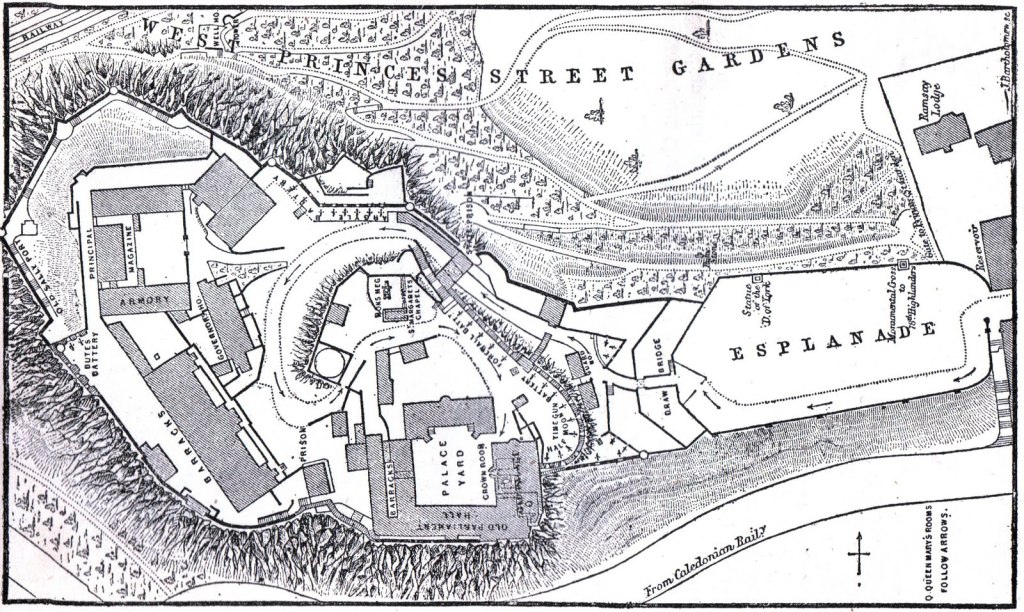

Edinburgh Castle was built upon the plug of an extinct volcano called Castle Rock, the summit rising to the height of 260 feet above the surrounding landscape. All sides are surrounded by sheer cliffs except for one readily accessible route where the ridge slopes more gently, and the castle is situated accordingly with several gates protecting the route to the summit. The first main defensive is the gatehouse featuring two statues of the Scottish heroes Robert the Bruce and William Wallace, with ‘Argyle tower’ and the portcullis gate being the second defense. Within the walls are the military barracks built in the 18th century accompanied by many war history museums. The Upper ward, at the highest point of Castle Rock, can be accessed via the 17th century ‘Fog’s Gate’. Within it are various buildings and gun batteries that surround the focal point of the castle, the Crown Square. Around Crown Square are the most popular attractions of the castle, including the Honours of Scotland (Crown Jewels), Scottish National War Museum, Royal Palace, and Great Hall. And lastly, at the very tippy-top of Castle Rock, is the oldest building Edinburgh: St. Margaret’s Chapel. King David I built it in the 12th century as a private chapel for the royal family and dedicated it to his mother, Saint Margaret of Scotland, who died in the castle in 1093.

Edinburgh has been called one of the most haunted cities in all of Europe. On various occasions, visitors to Edinburgh castle have reported their encounters with several peculiar spectres. A phantom piper, a headless drummer, the spirits of French prisoners from the Seven Years War, and colonial prisoners from the American Revolutionary War – even the ghost of a dog wandering in the grounds’ dog cemetery. The story of the phantom piper is an interesting one: legend has it that one day the people discovered a secret tunnel within Edinburgh Castle that stretched all the way down The Royal Mile road to Holyrood Palace two kilometres away. A lone piper volunteered to explore the tunnel whilst playing his bagpipes so that the others above ground would know where he was. The people followed the blaring of his bagpipes down The Royal Mile until all of the sudden the music stopped. Search parties were gathered to go into the tunnels after the piper, but no trace of him was ever found. It is said that one can still hear the sound of his pipes reverberating within the bowels of Edinburgh.

Crichton

We got a chance to explore Crichton Castle one sunny afternoon, thanks to our hosts Jane and Roger from Penicuik, Scotland. Roger had a wonderful singing voice and took some time out of every week to sing with his choir in the some of the many ancient, stone churches dotting the Scottish countryside. Crichton Collegiate Church was small, dark, and damp inside, therefore providing excellent acoustics. After listening for a few moments to the voices of angels, Ashleigh and I took off down the road through the plains to the nearby Crichton Castle.

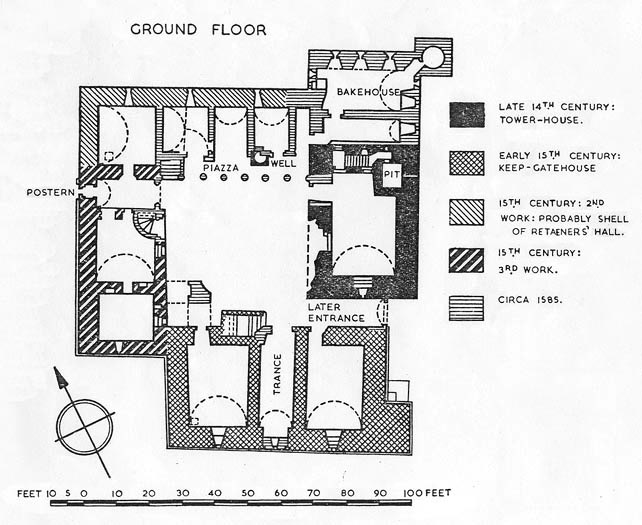

In 1406 Crichton Castle started out as a simple tower house that John de Crichton built and used as his family residence. John’s son William became lord of Crichton in 1443, and since then the castle had changed families a ridiculous amount of times over a short period. In 1483 William Crichton was forced to forfeit the castle (having been a supporter of some traitorous lord) and it was briefly given to a Sir John Ramsey who again forfeited it in 1488. King James IV then granted Crichton castle to a Patrick Hepburn who held it in his family for a few generations until Crichton was besieged and captured by the Earl of Arran in 1560. In 1568 the castle was once again passed on to another family, to a Francis Stuart, and with the Stuarts it remained until modern times.

Crichton Castle comprises of four contiguous buildings arranged around an inner courtyard. The 14th century tower, built by John Crichton, lies at the east of the castle and has a vaulted basement with timber entresol, and a vaulted hall above, although part of the tower has collapsed. William Crichton extended the castle in the early 15th century, building a second tower to the south, with the gate between the two towers. The south tower was entered by a door in the centre, with vaulted cellars either side. Two halls occupied the first and second floors. In the later 15th century a west block was added, with a six-storey tower at the south-west, containing several bedrooms. A stair in the south block gave access to these rooms. The north range was added at this time, closing the courtyard, but this section was heavily rebuilt in the following century. The castle’s most distinctive feature is its Italian-influenced courtyard façade, a fantastic wall with detailed diamond carvings which forms part of the north range. Francis Stewart, the designer, had travelled to Italy and was inspired by new styles in the buildings there. This was the source of the diamond rustication on the courtyard wall. The initials of Francis and his wife Margaret Douglas appear on the walls, together with an anchor representing Stewart’s position of Lord High Admiral of Scotland.

The ghost of a horseman has been seen riding up to the castle and through the original entrance, which has long since been blocked with stone. Some claim the phantom horseman is none other than Sir William Crichton himself, the first lord of Crichton castle. William Crichton is infamously known for organizing what historians like to call “THE BLACK DINNER” of 1440 (remind you of a certain Red Wedding perhaps?). Around that time the Clan Douglas was becoming quite powerful and William Crichton felt that his position as ‘Chancellor of Scotland’ was being threatened, in particular by the 16 year old earl, William Douglas of Tantallon Castle (eldest son of Archibald Douglas). One night, Chancellor Crichton invited William Douglas and his brother David to dine with him and King James II in Edinburgh. The Douglases, young and naïve, were lured to the castle and caught in a lethal trap. The head of a black bull was brought in, a symbol of death, the two young Douglases were beheaded in front of King James II on trumped up charges of treason.

Rosslyn

Rosslyn Chapel, made more well known by Dan Brown’s popular book “The Da Vinci Code”, is a Catholic chapel, built by the Sinclair family, filled and covered with intricate carvings created to tell stories to the unlearned and illiterate. As marvellous and interesting as that is, many people tend to overlook the ruins of Rosslyn Castle, just a few hundred metres down the road from the chapel, overlooking the North Esk River. The castle is now merely a shadow of what it was, but its ruins are still impressive. Part of the castle has been renovated into a holiday accommodation that can justly be described as unique. Upon arriving at its entrance I was especially blown away by the enormous stone arch bridge leading into the grounds.

The Sinclair family has owned the area of Rosslyn since 1280 and have yet to give it up, the castle and chapel still held under the name of Peter Sinclair, the seventh earl of Rosslyn. Way back in 1304 the first Rosslyn castle was built when the Sinclair family sought to strengthen their hold on their estates in the area. In 1452 there was an accidental fire and the castle was severely damaged, but eventually repaired. Again, Rosslyn caught fire in 1544, though this time because of a mean old Earl of Hertford who had his army bombard the castle during the “War of the Rough Wooing” (a war declared by Henry VIII of England, in an attempt to force the Scots to agree to a marriage between his son Edward and the infant Mary, Queen of Scots). In the late 16th century the Sinclair family managed to rebuild their precious fortress as well as adding a new five story east range built into the side of the rock face. In 1650 Rosslyn Castle suffered for the last time under the iron hand of Oliver Cromwell’s, “Old Ironsides”, invasion of Scotland, his artillery leaving the fortress in ruins, which is all you can pretty much find today.

Rosslyn Castle was once at a highly defensible location until the invention of longer range artillery. It is perched high on a promontory of rock, hidden in a wooded valley overlooking the beautiful River North Esk, just 8 miles from Edinburgh. It is surrounded on three sides by the river, and is only accessible by a narrow bridge crossing a 55-foot chasm! This high bridge was once wider and probably incorporated a drawbridge between two vertical piers. Beyond are the remains of the great gatehouse to the left and right of the entrance. Immediately to the left is the high stonework of the original ‘Wall Tower’, the earliest part of the castle built directly onto the lower scarped rock. A French-influenced two-storey house (now used as a holiday accommodation for rich tourists) to the left of the courtyard was built by a William Sinclair (not the same William who built Rosslyn Chapel) when he extended much of the castle in the late 16th century. His intials ‘WS’ with the shield bearing the Sinclair cross are still visible above the window on the first floor.

The stories claim, that within the vaults under the courtyard of Rosslyn Castle, there is a horde of treasure worth several millions of pounds. It is under the protection of a sleeping lady of the ancient house of Sinclair, who will only awaken by the sound of a trumpet, which must be sounded in one of the lower apartments. She will make her appearance and point out the spot where the treasure lies. If she could but be awakened, and point to the buried treasure, then Rosslyn Castle might rise once more from its ruins, and become the majestic pile that it once was.

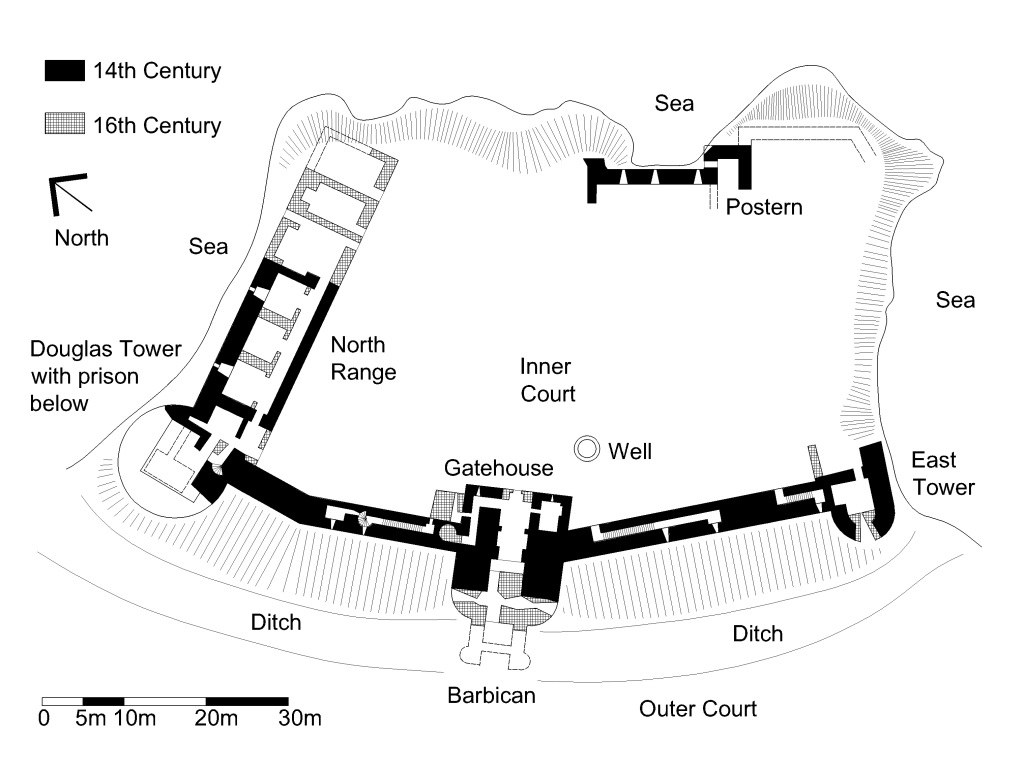

Tantallon

It was only through the generosity of our friends and neighbours that Ashleigh and I were able to visit more amazing castles than we were originally planning on. Roger brought us over to his friend Mike’s house one evening for tea and cookies. We sat in front of the fireplace while he told us stories about his exciting past; partly working for the Hudson’s Bay Company (a Canadian connection!) and about his grandfather who happened to be one of the survivors of the Titanic tragedy. Mike actually worked at Crichton Castle (a previously visited castle) as a tour guide, which granted him and up to four other people free access to all the castles in the Lothian area. He kindly offered to take Ashleigh and I on a small road trip one day to a couple castles, the first being Tantallon. The great ruin sat on the edge of the cliff overlooking the North Sea, and we had an exciting view climbing as high as we could up on the impressive curtain wall.

The earliest record of Tantallon Castle is a map, dated before 1300, marking the area with the name Dentaloune, which could be the corruption of an early Brythonic phrase ‘din talgwn’ meaning ‘high fronted fortress’. However, it wasn’t until around 1374 that William Douglas, owner of Tantallon after the convenient murder of his godfather, built the curtain wall castle which ruins are still seen today. The castle was built more as a status symbol than a line of defense, its design being outdated to the castles of the time. Tantallon Castle passed through many hands, but more or less stayed within the Douglas family, a family that caused a lot of trouble for the Scottish Crown. Around 1490, Archibald “Bell-the-Cat” turned against the Royal house and struck a treasonable deal with Henry the VII of England against James the IV of Scotland. In retaliation King James IV besieged Tantallon Castle but it did not suffer much damage as Archibald quickly submitted. Despite all of this, Archibald was back in favour as Chancellor of Scotland a couple of years later… to err’ is human, I suppose. A couple decades later the old Archibald died and his grandson, the new Archibald Douglas, became owner of Tantallon, and was far more annoying than the first. Together with his wife Margaret Tudor, they conspired to take her son, the young King James V of Scotland, to England. It was unsuccessful, and as punishment Tantallon was only taken away from Archibald for a year because he said he was sorry and asked for it back very nicely. In 1525, once again Archibald Douglas conspired against the crown with the support of the English king and took the young King James V into his custody, becoming Lord Chancellor of Scotland. Unfortunately for him, the King escaped to his mother in Stirling and banished Archibald north from the land. The impertinent Archibald Douglas didn’t obey, so King James V bombarded Tantallon Castle with cannons for 20 days, although the King’s guns could not be brought close enough to the walls to do substantive damage due to the deep outer ditch. The King lifted the siege and returned to Edinburgh, at which point Archibald Douglas counter-attacked and captured the King’s artillery. Realizing that he was in over his head, Archibald fled to England in 1529, leaving the castle to James. It was during this time that King James V added much to the castle, strengthened the tower, gate, and walls, leaving it closer to what it looks like today.

Tantallon’s castle design is unique in Scotland, its defences comprising of a single ‘curtain wall’, which is simply a massive barrier with a tower at each end and a heavily fortified gatehouse in the center. The curtain wall is 50 feet high, 300 feet long and 12 feet thick with several small chambers inside. The other end of the castle is protected by relatively small walls as the tall sea cliffs provide enough of a defense.

In March 2009, psychology professor Richard Wiseman released a photograph taken at Tantallon, which appeared to show a figure standing behind railings in a wall opening. The image, taken in May 2008 and sent to Wiseman as part of a research project, was described in The Times as showing a “courtly figure dressed in a ruff”. Wiseman stated that no costumed guides were present at Tantallon, and that three photographic experts have confirmed that the image had not been manipulated. Why don’t you judge for yourself, does this photo look ‘photoshopped’?

Dirleton

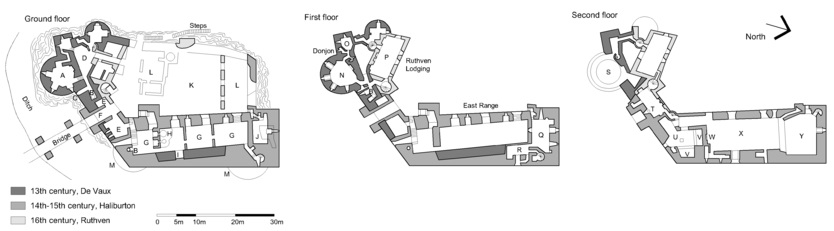

Dirleton Castle was the second stop on our tour generously hosted by Mike, only a 14 minute drive from Tantallon Castle. After passing through the gate into the grounds, we gazed about us in wonder as we trotted through the beautiful garden, full of marvellous flowers, up a path to a massive drawbridge. Inside, Dirleton was an intricate castle full of many rooms and passageways, even a creepy dungeon. The walls were crumbling and everything was in shambles, but we still had fun trying to imagine what everything would have looked like back in its heyday.

Dirleton Castle’s beginnings followed the Norman conquest of England in 1066, as previously mentioned, when the Norman de Vaux family settled there. Two de Vaux brothers were among a number of Anglo-Norman knights invited to Scotland, and granted land, by King David I in the 12th century. One of the brothers, John, was granted barony of the land of Dirleton, and proceeded to build two castles: Eldbotle was northwest of the modern Dirleton and Tarbet castle was on a nearby island. Neither of the original castles exist today. A couple generations later, another John de Vaux succeeded to the barony of Dirleton and in 1240 began construction of a fortress on the present location of Dirleton castle, part of which a stone keep that still stands to this day. This time of prosperity for John de Vaux ended in 1296 with the outbreak of the Wars of Scottish Independence. En route to the Scottish castle of Edinburgh, the infamous King Edward I “Longshanks” had Dirleton Castle besieged for several months until it was captured and garrisoned by English soldiers. It was only until 1314 that the castle was recaptured by the Scots and the defensive walls were deliberately destroyed to prevent its reuse by the English. The castle and the lands of Dirleton were eventually passed on to the Halburton family, through the marriage of the de Vaux family heiress, who carried out extensive works on repairing the castle walls, heightening the original towers, and adding a large hall and tower house.

Dirleton Castle stands on a natural rocky outcrop, a low ridge overlooking the farmland of East Lothian. It comprises a kite-shaped courtyard flanked by buildings on the south and east sides. The most substantial remains are the gatehouse, and the 13th century de Vaux family “cluster keep” to the south, while only the basement of the east range survives. The castle was originally approached from the south, via a bridge and drawbridge, across a 50 foot wide ditch. The oldest structure, the castle keep built by John de Vaux, comprises of a large round tower to the south and a smaller round tower to the west, with the two joined by a square tower.

No matter how hard I tried to squeeze the juice out of internet researching, there is absolutely nothing about hauntings, monsters, or even Harry Potter within Dirleton castle. It seems that the surrounding community lacks the imagination, or the superstitions, necessary to create a decent myth. Despite this, I would like to say that gazing through the gated pit into the deepest dungeon of the castle gave me more than the chills.

I have attempted to summarize each castle as much as possible, but it is difficult to quash hundreds of years of history, and so, despite the amount I have already written, THIS IS NOT THE END! Continue to Part II of this ‘Crash Course in Castles’.