Due to the large number of castles Ashleigh and I visited on our tour of the United Kingdom (16 in total!), and the vast amount of information attached to each, I have been forced to split my article into two parts. Welcome to PART 2! If you haven’t seen PART 1, please read it here.

The last outpost of Scotland awaited us next in the Shetland Isles! We visited a few English castles in Tamworth and Newcastle, the Scottish castle of Edinburgh, and others in the Midlothian region. Muness Castle on Unst Island, the most northern tip of land in Scotland, was to be our next stop, followed by Urquhart Castle on the waters of Loch Ness, Cuchulainn’s Castle in Ireland, and Beaumaris, Caernarfon, Conwy, Rhuddlan, and, finally, Flint Castle in Wales. Each one of these imposing strongholds had their own stories to tell, through their importance in history, the way they were designed, and the legends surrounding them.

Muness

Arriving at the gloomy, stormy Shetland Isles on a rocking boat of sea-sickness, our high hopes for an exciting and eventful stay were soon dimmed. The tiny and most northern island of Unst at first glance seemed barren of life, trees included. For the first few weeks the weather was the absolute worst, wind and rain so powerful you couldn’t step outside for a breath of fresh air. But when the days started improving and we began to cautiously venture out on our ramshackle bicycles to explore, we soon discovered that the island of Unst was an archeologist’s treasure trove of Neolithic burial cairns, Viking longhouses, standing stones, and even a castle of its own.

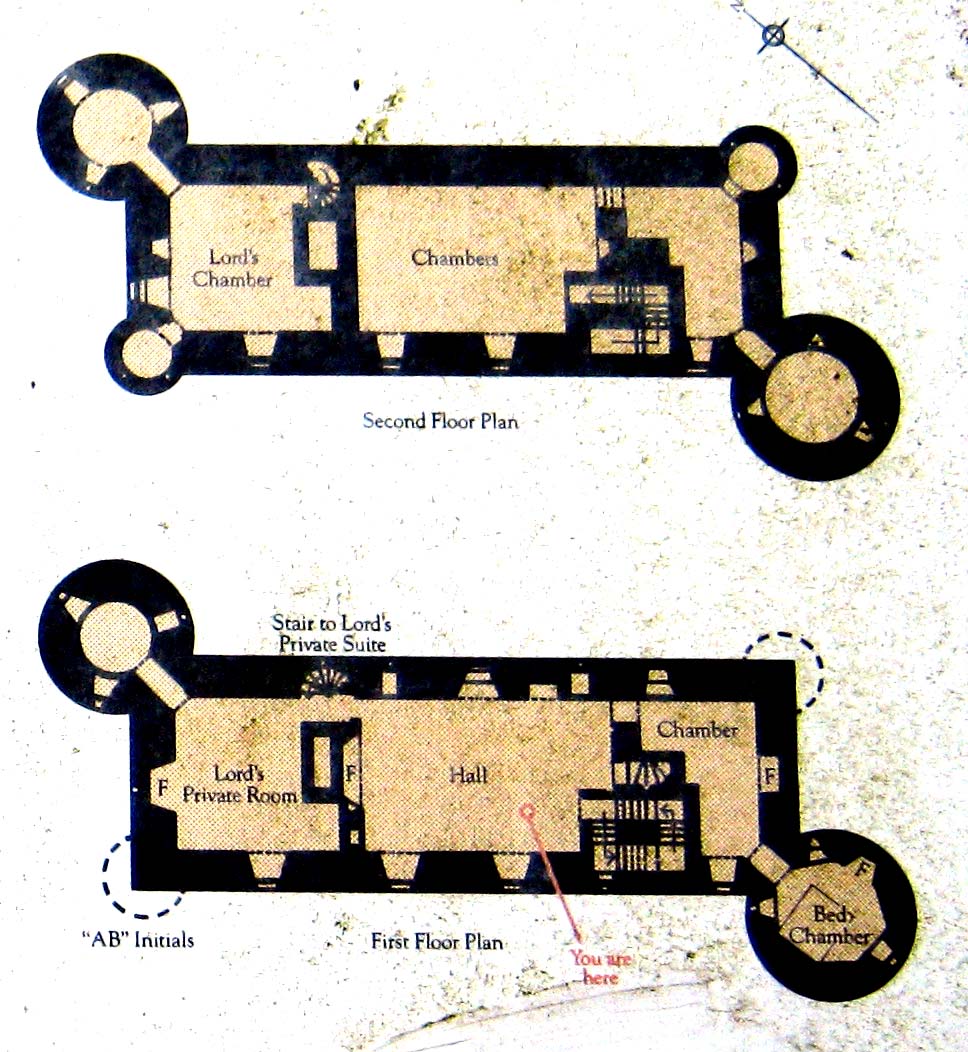

Muness Castle, the most northerly fortalice in Britain, was built in 1598 by the newly appointed Chamberlain of Shetland, Laurence Bruce. Laurence, originally from southern Scotland, thought the Scandinavians in Shetland were ‘lesser people’, and had no qualms in exploiting them to their fullest potential. Similar to the Sheriff of Nottingham villain in “Robin Hood”, Laurence Bruce raised the taxes to an exorbitant amount and soon became filthy rich off of the poor Shetlanders. Laurence also took a cut of the profits made by Dutch merchants who bought low and charged high prices for goods sold to the inhabitants. If that’s not enough, evidently Laurence Bruce helped himself to the local women, and is believed to have fathered approximately twenty-four illegitimate children beyond his ten legitimate children. The Chamberlain rested safe in the knowledge that the Earl of Orkney, his overlord, seldom bothered with visiting the Shetlands, and he acted without fear of reprimand. After the construction of Muness Castle, however, The Earl of Orkney found the fortress to be a direct challenge to his authority, seeing as Laurence didn’t bother asking permission from him to build it. The Earl prepared a force to attack Muness, but was dissuaded by his family as Laurence Bruce was actually of a distant relation (unfortunately for the Earl). In 1627, to the joy of many, the evil Chamberlain got what was coming to him when a dreadful pirate ship from Normandy came out of the mists and destroyed large chunks of Muness Castle.

What’s left of the castle lays in relatively intact ruins, though now only two stories high rather than three. Muness was built in a “z” formation with two circular towers at diagonally opposite corners (like a “z” shape… in case that wasn’t clear) and originally had a walled courtyard on its southern side, but that was destroyed long ago. Muness castle was not only built as a manor and home for Laurence Bruce, but also as a defensible fortification complete with gunloops to defend himself from, well, everyone that hated him.

There have been whispers of a spectral haunting within castle Muness, that is, a few vague rumours on the internet. Something about a shadow dressed in a frilly waistcoat and breeches? The island of Unst, however, is home to a much older legend of a ‘White Wife’ that materializes in people’s vehicles coming from Uyeasound (a five minute drive from Muness) towards Baltasound. As the story goes, if you are a young man driving alone along that road at night you have a chance of meeting her ghost. It is rumoured that the White Wife is looking for her son and will never rest until she finds him. On the side of the highway there is a standing stone with a face, supposedly marking where the white woman’s spirit appears. Vallhala Brewery, on the island of Unst, has taken this old legend and decided to make an exciting new beer out of it; the ‘White Wife’ is a light, golden ale, with a delightfully fruity after-taste.

Urquhart

Our final stop in Scotland was at the ultra-famous Loch Ness. Interested in the idea of spotting the Loch Ness monster, we decided to spend the night camping along its shores. We found a lovely, not-so-legit camping spot with a pebble beach, grassy knolls, possibly some grazing sheep, and immediately next to us were the ruins of Urquhart Castle. Despite being surrounded by Japanese tourists, Urquhart is a picturesque beauty resting on an outcrop of land, called “Strone Point”, jutting out into the loch. The castle, though in a bit of a ruined state, is a massive tourist attraction– second to “Nessieland”.

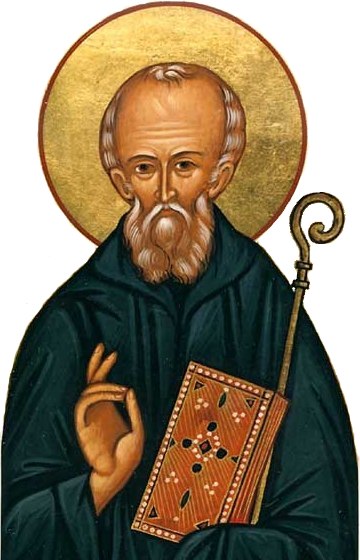

Although the present ruin of Urquhart Castle was built in 13th century, the site of Urquhart was once occupied by a fortress named “Airdchartdan” as early as the 5th century. It was recorded in the history books that an Irish missionary, Saint Columba, visited the town of Inverness in Loch Ness between 562 and 586 AD. During the same visit, Columba stayed at Airdchartdan and converted a Pictish nobleman named Emchath, whom we can assume was the lord of the fortress at that time. Emchath was on his deathbed and the promise of eternal paradise after death sounded like a good option. Emchath’s son, Virolec, and his whole family converted to Christianity as well, just to be encouraging.

The present day castle of Urquhart was first founded in the 13th century by Alan Duward, the Hostarius (protector of the King’s property) of King Alexander II, to maintain order within the “Great Glen”. In 1296, King Edward I, or Edward ‘Longshanks’, captured Urquhart castle– kicking off the Scottish Wars of Independence. Edward Longshanks appointed Sir William FitzWarin as constable to hold the castle for the English, but he failed miserably when in 1298 the Scots attacked and reclaimed Urquhart. Be that as it may, this being a very turbulent time for castle possession in the history of the United Kingdom, Urquhart was retaken under the command of Edward I in 1303. Finally, in 1307, Robert the Bruce marched through the Great Glen and captured the castles of Inverlochy, Urquhart, and Inverness, all of which remained in Scottish hands from then on. After this time Urquhart became a royal castle, held for the crown by a series of constables, but the fun was still not over. A new enemy arose, the Lords of the Isles, the MacDonald clan, who consistently raided the Great Glen and Urquhart castle in the late 1300’s and subsequently over the next 200 years. Though some attacks were successful, the MacDonalds were never able to hold Urquhart for long.

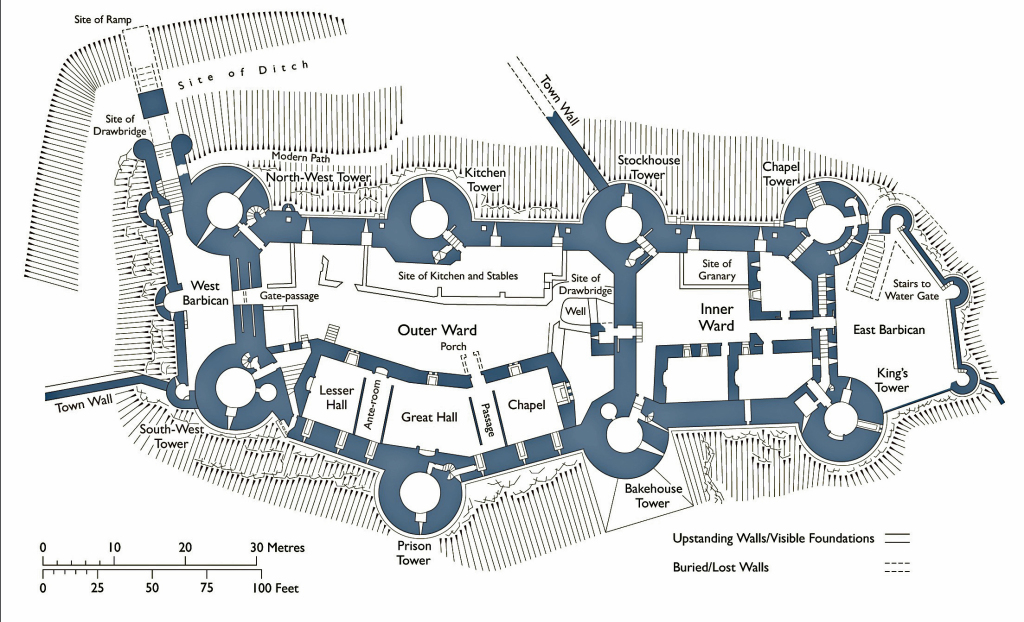

Urquhart castle is situated on the north-west side of the Loch Ness, commanding the route along that side of the Great Glen. The castle is quite close to water level, though there are low cliffs along the north-east sides, and a dry moat protects the fortress from and inland approach. The walled portion of the castle is shaped roughly like a figure-8 forming two baileys (enclosures): the Nether Bailey to the north, and the Upper Bailey to the south. The Nether Bailey is protected by a gatehouse containing two towers flanking an arched entrance passage complete with a portcullis. The Nether Bailey has been the focus of activity on the castle since around 1400 and contains the main castle keep as well as a range of other buildings (the Great Hall, private chambers and kitchens). The Upper Bailey was placed on the mound where the earlier fortress of Airdchartdan once stood. A 16th-century water gate in the eastern wall of the Upper Bailey gives access to the shore of the loch and adjacent buildings may have housed the stables, smithy, and a pigeon house.

Though Urquhart castle is a venue on the Loch Ness worth visiting, it is overshadowed by a popular and far more renowned tourist attraction located deep within the loch. A “Cryptid”, from the Greek word krypto meaning “to hide”, is a creature whose existence has been suggested but not yet discovered or proven by the scientific community. Among the most famous of these are the Yeti in the Himalayas, the Sasquatch in North America, the Chupacabra in Latin America, and the Loch Ness monster in Scotland. The story of the Loch Ness monster has been around for a long time, one account dating back to year 565. Saint Columba, the Irish missionary who visited the fortress Airdchartdan at the site of the later Urquhart castle, came across the local Picts burying a man by the River Ness. They explained that the man had been swimming across the river when a terrible water monster rose up from the depths and attacked him. The locals tried to save the man but by the time they pulled him out of the river he had already been mauled to death by the creature. Hearing this, Saint Columba leapt at the chance to impress the pagan Picts with his magic Christian powers. Columba sent one of his followers, Luigne moccu Min, to swim across the river. The evil creature rose up from the depths yet again to attack a human trespasser, but Saint Columba made the sign of the cross and commanded, “Go no further. Do not touch the man. Go back at once.” The beast immediately halted as if it had been pulled back with ropes and fled to the pits of Hell from whence it came. The pagans, realizing that being Christian gives you supernatural powers, immediately converted and gave praise to God. Ever since that time and up to now there have been sightings of the Loch Ness Monster, often described much like the ancient plesiosaur– a creature with flippers, a 6-9 metre-long body, a long neck and a small head.

Cuchulainn’s Castle

Following the path of “Cuchulainn”, an Irish folk hero and mythological warrior, was one of the many exciting adventures we experienced on our quick jaunt through the Emerald Isles of Ireland (read more about it here). From birth to death we followed Cuchulainn’s epic story to real life places in the Irish region of Louth, a land famous for its legends. Our final destination on that particular journey was the town of Dundalk, where it’s said that the mighty Cuchulainn spent his childhood and grew up to become a great hero.

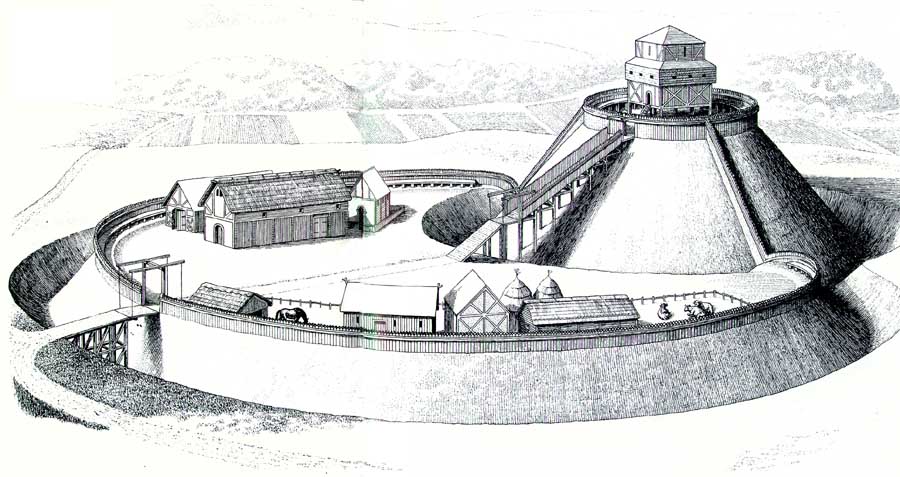

Just outside the modern town of Dundalk stands a tall but relatively small fortress upon a huge, 10 metre high earthen mound, encircled by a wide ring of earth. Though it is believed that the original village of “Dún Delga”, where Cuchulainn was born, once flourished around the site of the castle, the earthwork defenses and the tower on its summit are both from an entirely different age. Around 1180 an invasion force of Normans, having arrived in Ireland, created the earthen defenses at Dún Delga (that still exist to this day) as part of their “motte-and-bailey” castle. It was only much later, in 1780, when the Gothic-style fortress seen today was built by a local merchant named Patrick Byrne. Patrick was also known to have done a bit of smuggling on the side, which is why some call it the Pirate Byrne Castle.

Cuchulainn’s Castle is a perfect example of a ‘motte-and-bailey’ design. During their invasion of Britain in 1066, the Normans designed an effective fortress that was cheap, easy, and quick to build with an unskilled workforce. The Normans conquered lands as their armies swept along the United Kingdom and swiftly raised these motte-and-bailey castles to maintain their dominance. The Norman fort would have been a timber tower built upon the “motte” or mound, with an enclosed courtyard or “bailey”, surrounded by a defensive ring of earth and an outer ditch. Cuchulainn’s Castle, the stone tower built by Patrick Byrne, was created principally as a display of wealth and a summer home for the rich Mister Byrne, not as a defensible fort.

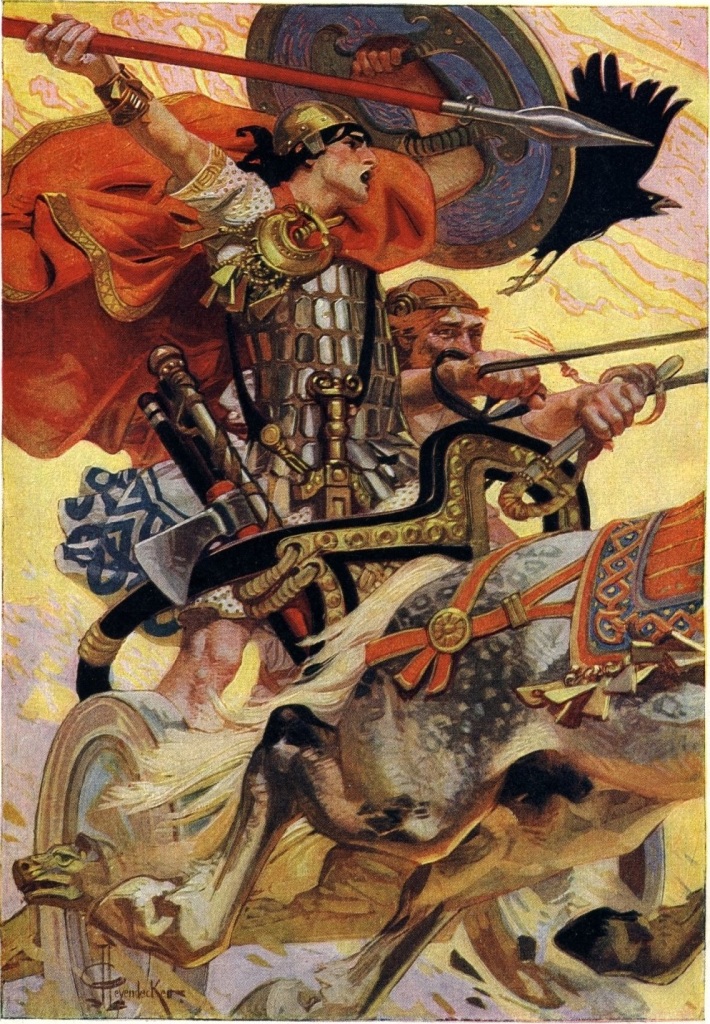

It was around the time of Christ when the stories of Cuchulainn around Dún Delga took place. It is written in the Ulster Cycle that the great hero Cuchulainn single-handedly fought off invaders into the land of Ulster whilst all the other fighting men were lying in bed, sick from a curse. In the tale, “The Cattle Raid of Cooley”, Queen Medb of Connaught sought a prized bull from the town of Cooley in Ulster and would stop at nothing to retrieve it. When bribery didn’t work, she gathered a massive armed force of 9000 men and declared war on the Ulstermen, completely confident in her victory. As Queen Medb marched on Ulster, Cuchulainn picked off the enemy one by one with his sling, day after day, and would challenge all of Medb’s greatest warriors to single combat. After much grief and the deaths of thousands, Cuchulainn managed to stall Medb’s army long enough for the warriors of Ulster to awaken from their curse and rise to battle. What was left of Medb’s army was beaten back and forced to retreat, leaving the land of Ulster safe from harm.

Beaumaris

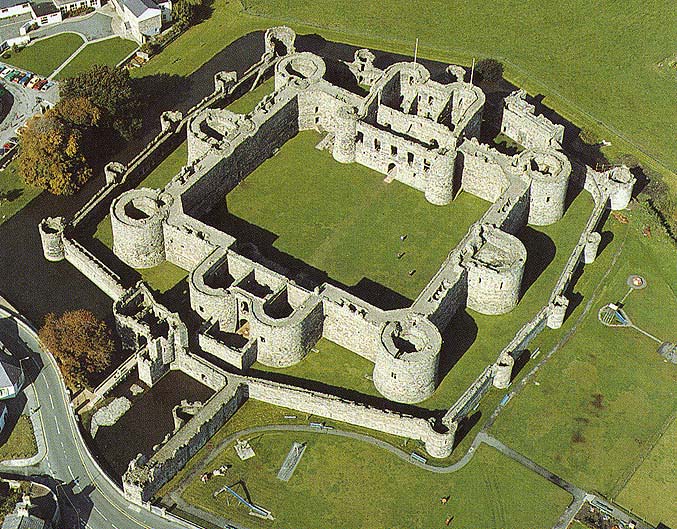

Catching the ferry from Dublin, Ireland we arrived in Holyhead, Wales and were promptly greeted by an extra-friendly Welshmen who informed us (in an amusing accent) of all the amazing castles there were to see in the area. We met up with Ashleigh’s brother, Braeden, (who had been on his own Euro-trip) and embarked on one last whirlwind tour of British castles before leaving the land of tea and crumpets behind. The first stop was Beaumaris Castle, pronounced exactly like a butchered French name (bow-mare-is), only a short bus ride across a bridge to the Isle of Anglesey. When one thinks of a typical castle, Beaumaris is exactly as it should be: a draw bridge, a moat (crocodiles would have been nice), and plenty of towers; I was thrilled to have finally found a proper, medieval stronghold.

Numerous megalithic monuments and menhirs are present on the Isle of Anglesey–evidence of human occupation since long before history was written. It is known that the island was once a religious centre for the Celtic Druids, but in 60 AD a Roman general named Gaius Suetonius Paulinus attacked the island in an attempt to break the power of the Druids. The shrines and sacred groves were destroyed, the Druidic priests were slaughtered, and eventually the Isle of Angelsey was brought into the Roman Empire. Hundreds of years later, Beaumaris Castle was built on the site as part of King Edward I’s campaign to conquer Northern Wales, the first of five castles we visited built by Edward– that busy bee. The kings of England and the Welsh princes had vied for control over North Wales since the 1070’s and the conflict had been renewed, leading to Edward’s intervention in 1282. Edward’s vast army and resources made him unstoppable, and he soon colonized northern Wales, establishing three new English shires: Caernarfon, Merioneth, and Anglesey. In 1294 the Welsh rebelled against English rule under the command of Madog ap Llywelyn (oh what a funny name), and a bloody rebellion commenced within the new English shires. The iron boots of Edward Longshanks crushed all resistance over the winter and by the time spring came around peace was re-established under English rule. Noticing a weak spot in Anglesey, Edward sought to fortify the area and chose a site called “Beaumaris” to build his castle. Work on the fortress commenced in 1295, but due to financial difficulties, and then even MORE financial difficulties when Edward’s attention turned to invading Scotland (wars can be sooo costly), the work plodded along for 35 years. At last the money dried up and in 1330 the construction halted, leaving the castle unfinished. After that, Beaumaris Castle became the stage for a few more rebellions. The castle was captured in 1403 during a second Welsh revolution, but lost back to the English. Then again it was used as a base for the Royalists during the English Civil War in 1642, but surrendered to the Parliament in 1646. After the war many castles were ‘slighted’, damaged to put them beyond military use, but the Parliament was concerned about a Royalist invasion from Scotland and Beaumaris was spared (lucky for us). Nowadays the castle is in good condition and can be enjoyed by wave after wave of countless tourists and school field trips.

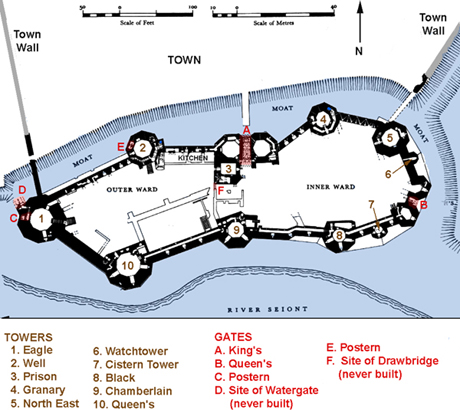

Beaumaris castle is a fine example of perfect symmetry, unlike most fortresses, with each tower and parapet having a twin. This basic castle design consists of an inner wall and an outer wall. The inner wall is considerably more massive, square in shape with six towers and two huge gatehouses, one left unfinished. The inner ward was intended to hold accommodation and other domestic buildings, though they were never built. The outer defence consists of an eight-sided curtain wall with twelve towers and two gateways, one leading out to the north side of the castle and the other into the surrounding moat with accessibility to the sea. The sea gate and dock were protected by another outer wall and a firing platform that may have housed a trebuchet siege engine during the medieval period.

Before the Romans conquered much of southern Britain (including Anglesey), the Druids held much of the power in the country as religious leaders. Not much is known about the Druidic religion, but through accounts of various Roman historians they often conducted human and animal sacrifice, claiming to read the future in the entrails or by the way the bodies convulsed as they died. When the Romans set about to conquer Britannia they saw the Druids as a threat to their authority and sought to wipe them out. General Gaius Suetonius Paulinus’ invasion of Anglesey, on the site of Beaumaris, was a huge hit to the Druidic community. Tacitus, a military writer, scribed an account of the Roman/Druid battle as follows:

“[Paulinus] prepared to attack the island of Mona (Anglesey) which had a powerful population and was a refuge for fugitives. He built flat-bottomed vessels to cope with the shallows, and uncertain depths of the sea. Thus the infantry crossed, while the cavalry followed by fording, or, where the water was deep, swam by the side of their horses. On the shore stood the opposing army with its dense array of armed warriors, while between the ranks dashed women, in black attire like the Furies, with hair dishevelled, waving brands. All around, the Druids, lifting up their hands to heaven, and pouring forth dreadful imprecations, scared our soldiers by the unfamiliar sight, so that, as if their limbs were paralysed, they stood motionless, and exposed to wounds. Then urged by their general’s appeals and mutual encouragements not to quail before a troop of frenzied women, they bore the standards onwards, smote down all resistance, and wrapped the foe in the flames of his own brands. A force was next set over the conquered, and their groves, devoted to inhuman superstitions, were destroyed. They deemed it indeed a duty to cover their altars with the blood of captives and to consult their deities through human entrails.”

Caernarfon

Upon entering the seaside town of Caernarfon we were astonished and delighted by the sheer grandeur of its castle. There were eight massive towers (with smaller turrets crowning those towers), an impenetrable gatehouse, a colossal curtain wall with many twisting passages, two main gates, and even a water gate to the Seiont River– this castle had it all. We had two hours to explore and we didn’t even finish due to the sheer size of this fortress. Caernarfon, becoming the capital of the Northern Wales after its conquest by King Edward I, was built not only to protect the capital city, but also as a major symbol of English authority and power.

Long before Edward’s time, when the Romans occupied southern Britain, there was a fort and settlement called ‘Segontium’ on the outskirts of the modern town Caernarfon. Segontium was positioned near the bank of the River Seiont, due to its sheltered nature and also as boat traffic up the Seiont would have been able to supply the fort. Little is known about the fate of Segontium after the Romans departed from Britain in the early 5th century, but it is written in history that during the construction of Caernafon Castle a tomb was uncovered that the Romans left behind, the final resting place of Emperor Magnus Maximus. In legend, Emperor Maximus had dreamt of a fortress, “the fairest that man ever saw”, within a city at the mouth of a river and opposite an island. Could this have been a prophecy of the future Caernarfon castle? King Edward I seemed to think so, and in 1283 he began to work on one of the most magnificent and imposing castles in the British Isles. In 1294, Wales broke out in rebellion under the leadership of Madog ap Llyweyln and Caernarfon was a priority target. Unfortunately for the English, the castle wasn’t even close to completion and its defences were deplorable. It was quickly captured and anything flammable was set alight, including the rest of the town. It wasn’t long, however, until English forces moved in to retake Caernarfon, clean up the mess, and begin rebuilding what was destroyed. Afterwards, work on Caernarfon castle began anew and continued at a steady rate until 1330 when King Edward I ran out of money, moved on to more important matters, or simply gave up on his castle building crusade in Wales. Just like Beaumaris castle, Caernarfon was besieged in 1403 during the “Glyndŵr Rising” a second Welsh revolution led by another man with a funny name. The French, jumping at any chance to irritate the English, decided to lend a hand, but this time Caernarfon was a fully-functional battle station and the siege proved unsuccessful. Caernarfon was also garrisoned by Royalists during the English Civil War in the mid-17th century and was besieged three times during that war. After being surrendered to Parliamentarian forces in 1646, Caernarfon castle retired from action. Decades later, the castle and town walls were ordered to be dismantled, but everyone quietly decided amongst themselves that it would be far too much stone to move and the work never got started. Through turbulent times and threat of destruction, the castle has survived in good condition and still retains its formidable stature.

Caernarfon Castle was built to be an impressive symbol of the new English rule in Wales. It is believed that the design of the castle was a representation of the Roman Walls of Constantinople; the castle towers are polygonal rather than round. The conscious use of imagery from the Byzantine Roman Empire was an assertion of authority by Edward I, influenced by the legendary dream of the previously mentioned Roman Emperor, Magnus Maximus. Caernarfon’s walls were built as two separate enclosures, east and west wards, which roughly form a “figure eight”. The divide between the two wards was supposed to be established by a range of fortified buildings, but they were never built. All the towers, battlements and firing galleries made Caernarfon Castle one of the most formidable concentrations of fire-power to be found in the Middle Ages. The Eagle Tower at the western corner of the castle was once the grandest; it has three turrets which were once surmounted by statues of eagles, another symbol of Roman supremacy, though the remains of these statues are hard to make out. At the basement level there was a water gate through which visitors travelling up the River Seiont could enter the castle. The main entrance from the town is the grand, twin towered King’s Gate that, if it was completed, would have been protected by two drawbridges, six portcullises, a right-angle turn before a lower enclosure, as well as many arrow loops and murder holes along the way. The Queen’s Gate, also left unfinished, was meant to give direct access to the castle without having to proceed through the town. King Edward I had big ideas when it came to his castles but it seems he was never able to complete them.

One of the most famous tales in the world, first written by Geoffrey of Monmouth, had a profound effect on the Welsh people and medieval politics. The legend of King Arthur was extremely popular during that era, especially among the Welsh, who believed in the prophecy of a messianic King who would return from death to banish all enemies from their land. Edward I knew all about the legends of the “one true king of Britain” and used it to his benefit. In fact, the notion of Arthur’s eventual return to rule a united Britain was adopted by all the Plantagenet kings from 1154 to 1485, including Edward, to justify their rule. Once the ancient King Arthur had been safely pronounced dead and buried at Glastonbury, in an attempt to deflate Welsh dreams, the Plantagenets were then able to make ever greater use of Arthur as a political cult to support their dynasty. “Relics” of King Arthur were collected by Plantagenets, including Arthur’s magical sword Excalibur by Richard I, Arthur and Queen Guinevere’s bones by King Henry II, and Arthur’s crown by Edward I. Similarly, ‘Round Tables’ – jousting and dancing in imitation of Arthur and his knights – occurred at least eight times in England between 1242 and 1345, including one held by Edward I in 1284 to celebrate his conquest of Wales and the ‘re-unification’ of Arthurian Britain. It is said that the design of Caernarfon castle, drawing on the imagery of Roman sites around Britain, was also Edward’s intent of creating an allusion of his Arthurian legitimacy.

Conwy

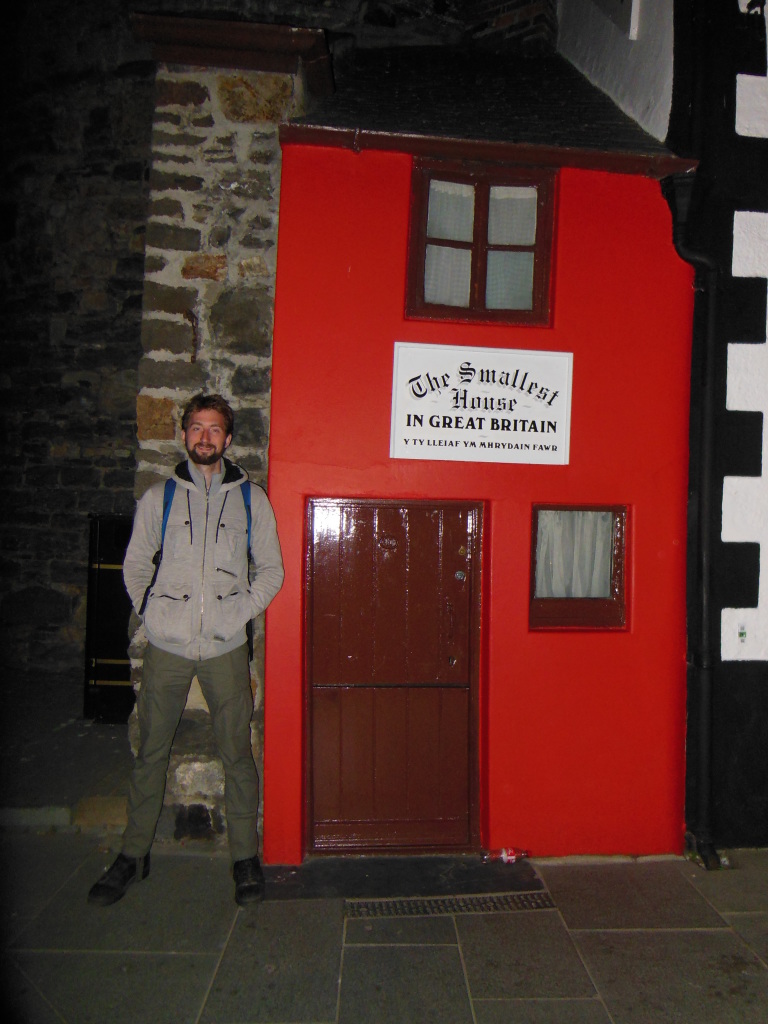

At last we arrived in Conwy for Friday night and had a milkshake thrown at our heads. Not the kind of greeting I had expected but I took it as it was. Young partiers were driving their fancy cars down through the ancient gates of this walled town, vibrating over cobblestone streets and nearly scraping historical buildings along the way. Just as it was in the Middle Ages, the town of Conwy is contained within relatively intact fortifications and overlooked by yet another Edwardian castle placed dramatically on a hill. We set up our tent on the outskirts of town for the night (in some kind of hobo-bush), and the next morning we eagerly invaded Conwy’s defences, taking time to walk around the whole village along the battlements. After meandering through town (and spending a moment to get a picture beside the smallest house in Britain) we arrived at the castle gates, and stood captivated by its lofty spires and daunting barbican.

Just like all the other castles in Northern Wales, Conwy was built by King Edward I to help maintain English control over the conquered Welsh. A Welsh Abbey named Aberconwy once existed on the site of Conwy, and when Edward I marched into North Wales in 1283 he captured and relocated the abbey. The act of building a settlement upon such a high status Welsh site was a symbolic demonstration of English supremacy by Edward (not to mention it was pretty mean). The plan of building Conwy’s town walls and castle commenced immediately, and only four years after the invasion, Conwy’s defenses were complete. Unlike its brothers at Beaumaris and Caernafon, Conwy was prepared for the Welsh rebellion in 1294 and withstood the siege of Madog ap Llywelyn. During the second Welsh revolution in 1400, under the leadership of Owain Glyndŵr, the Welsh used their wits rather than sole force to capture Conwy. Owain’s cousins, Rhys ap Tudur and his brother Gwilym, pretended to be carpenters working on repairing the castle. The trick worked; the watchmen on duty naively allowed their entry into the stronghold and the brothers proceeded to kill the guards, seizing the castle. Welsh rebels consequently attacked and captured the rest of the walled town. The brothers held out there for three months before negotiating a surrender, and as part of this agreement the pair were granted a royal pardon. In 1642 the English Civil War broke out, and just as with Beaumaris and Caernafon castle, Conwy was garrisoned by Royalists loyal to King Charles. John Williams, the Archbishop of York, took charge of the castle on behalf of the king, and set about repairing and garrisoning it at his own expense. A few years later, a Sir John Owen was appointed governor of the castle instead of Archbishop Williams despite all of his hard work, leading to a bitter dispute between the two men. Feeling unappreciated, the Archbishop defected to Parliament, and the town of Conwy fell in August 1646 to Parliamentarian forces. Conwy castle encountered no more battles, but over time the castle had been left to rot and fell into ruin, leaving only the stone fortifications behind.

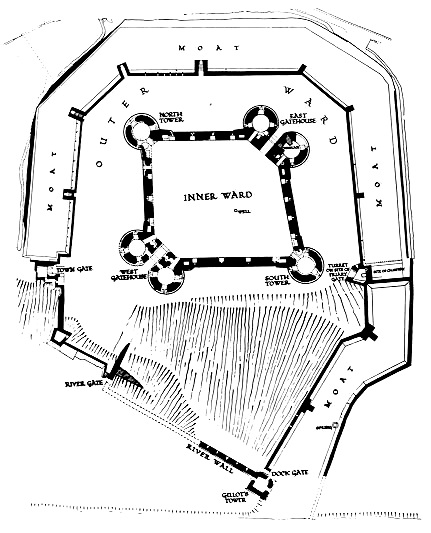

Conwy Castle hugs a rocky, coastal ridge overlooking what was once an important crossing point over the river Conwy. The castle has a rectangular plan and is divided into an Inner and Outer Ward, with four 70-foot tall towers on each side. The main entrance to the castle is through the western barbican, an exterior defence in front of the main gate, and leads into the Outer Ward. The Inner Ward, which would have contained chambers for the royal household, was originally separated from the Outer Ward by an internal wall, a drawbridge and a gate. The Inner Ward was designed so that in times of emergency it would be sealed off from the rest of the castle and supplied from the eastern gate by sea almost indefinitely. When building a castle, its location and the strategy of its defences are paramount, and could even decide the rise and fall of ruling powers!

Another popular attraction within the heart of Conwy is ‘Plas Mawr’, a great hall built between 1576 and 1585 for the influential Welsh merchant, Robert Wynn. Plas Mawr is a beautiful and ornate townhouse left behind from the Elizabethan era, an architectural gem that reflects Robert’s wealth and status amidst the Welsh gentry. As successful as he was, there is a tragic story of Robert Wynn’s pregnant wife Dorthy and his young son. One night, after watching from the tower awaiting Robert’s return, Dorthy accidentally slipped down the spiral, stone steps while carrying her son, severely injuring them both. The servants of the house hastily carried them to Dorthy’s bedroom and called the family doctor. Unfortunately, their usual doctor was otherwise engaged, so a more junior doctor was sent to examine them both. When the junior doctor saw just how badly Dorthy and her son were wounded, he panicked—frightened that he didn’t have enough experience to treat them. When he attempted to leave the servants grew angry and locked the doctor in the room, forcing him stay with the wife and child. When Robert Wynn finally arrived home and was told of the disaster, he rushed to the bedroom only to find that the doctor had escaped and his wife, premature baby, and child were dead. Filled with rage at the careless doctor for abandoning his family, he vowed to hunt him down. The bereaved husband search was fruitless and eventually he went mad with grief, killing himself. It is said that Robert’s spirit still seeks the missing doctor in the room where his pregnant wife and child died.

Rhuddlan

When we first laid eyes on Rhuddlan castle, one of the last few stops we squeezed into our tour, we immediately asked ourselves, “Did a bomb go off here?” A great, gaping hole yawned in one of its bulwarks, half a tower was missing, and many stones looked as if they were ripped from the walls. ‘Swiss cheese’ could accurately describe Rhuddlan’s defenses. Steel spiral staircases and platforms were added so that tourists could walk partially on to the battlements because there was nothing else to step on. Compared to our previous castles in Conwy and Caernafon, Rhuddlan was merely a skeleton of the past in a derelict state. Though ruined, Rhuddlan castle wasn’t any less interesting, and it was certainly beautiful sight to behold– in its own way.

Many years before the Edwardian castle and the Norman occupation, Rhuddlan was the heart of the country. From here all the Lords of Rhuddlan ruled over North West Wales. In the late 11th century, the Normans invaded after conquering England. The remains of a Norman castle at Twthill, built in 1086, is just to the south of the current Rhuddlan castle. It was July, 1277 when King Edward I left Chester, England with a force of men, launching his invasion of Northern Wales. Flint and Rhuddlan castle were the first of his “Iron Ring”: a chain of fortresses designed to encircle North Wales and dominate the Welsh. The construction of Flint castle began immediately, followed by Rhuddlan castle three months later. In five years the castle was completed, and in 1284 the Statute of Rhuddlan was signed at the castle, surrendering all the lands of the former Welsh Princes to the English Crown and introducing English common law. Rhuddlan castle successfully defended itself through two Welsh uprisings (though the town was badly damaged) but after the English Civil war the Parliament ordered for Rhuddlan to be slighted, partially demolished to prevent further military use. It is because of this slighting that Rhuddlan castle lies in such a ruined state, and one can only reminisce of its former glory.

Rhuddlan castle is simple but has a unique diamond design with the two gatehouses positioned at the corners rather than along the sides. An inner ward was protected by those gatehouses and towers, whereas the outer ward was defended by a smaller wall and towers, part of which still exists near the river Clwyd. During construction the river course was straightened and dredged to allow ships to sail inland along a man-made channel. Its purpose was to allow provisions and troops to reach the castle even if hostile forces prevented overland travel.

There is an old story that takes place at the site of Rhuddlan when the Welsh lords were still in power. Long ago, the beautiful daughter of the King of North Wales, Erilda, was betrothed to the Prince of South Wales, a marriage intended to create peace between the two ancient nations. One day, while following the royal hunt, Princess Erilda became lost deep in the woods. Just as it was getting dark and she was starting to despair, a figure rode out from the shadows on a huge steed, clad in black armour. He lifted her into his horse and carried her back to her father’s castle at Rhuddlan. The anxious king was overjoyed when the black warrior, with blood-red plume upon his helmet, rode into the courtyard with his rescued daughter. All was not well, however, for the black knight was truly an evil spirit, determined to sabotage the peace between north and south Wales. The knight cast a spell upon the princess, and she found herself unable to resist when he suggested that she elope with him. As they made their way towards the nearby river, the knight reverted to his true form. The princess recoiled in horror at the monstrous demon to which she was about to plight her troth. Seizing Erilda in its scaly arms, the evil creature dragged the princess screaming into the river Clwyd, disappearing below the water’s surface forever. It is said that to this day Rhuddlan castle is haunted by her blood curdling screams and the demon’s laughter.

Flint

The day was getting late and Flint castle was our final stop, the last castle we ever saw in Great Britain, last… and possibly the least. It wasn’t much to look at compared to what we had seen, and the gate was closed so we weren’t even able to enter. Little did I realize just how significant this castle really was.

Flint was the first Edwardian castle built and the starting point of England’s invasion and colonization of Wales. The site was chosen for its strategic position: only one day’s march from Chester, supplies could be brought along the River Dee, and there was a ford across to England that could be used at low tide. 1800 labourers and masons began work in 1277 and finished in 1286, but not before Welsh forces besieged the castle in an attempt to uproot the English from their land. Even with the defences unfinished, the English managed to repel the attack and continue building Flint castle. In 1294 Flint was again attacked by the Welsh during the Madog ap Llywelyn rebellion. In a desperate attempt the constable of Flint set fire to his own castle to prevent its capture by the Welsh, “I’d rather be dead than see this castle in the hands of the Welsh!” He shrieked over the sound of burning timber, “Never trust a Welsh!” (Of course we all know that the Welsh are an excellent people, salt of the earth, truly). With the conclusion to the Welsh Wars, English settlers were given property titles in the new town that was laid out in front of the castle to promote English colonization. When the English Civil War came around, Royalists garrisoned in Flint castle and held it until 1647. Parliamentarian forces besieged the fortress for three months until the Royalists gave up and surrendered. Oliver Cromwell’s order to destroy every castle, preventing its reuse in conflict, was carried out at Flint, leaving the site of decay we find today.

Before Flint castle was slighted it was quite an impressive structure with a design unique to the British Isles. The castle was based on medieval French models where one of the corner towers is enlarged and isolated, serving as both a guard tower and a keep. Though small, Flint castle was built strong and sturdy with seven metre thick walls at the base and five metres at the top. Access was gained by crossing a drawbridge into a central entrance chamber on the first floor. A vaulted passageway would have run from the inner ward straight to the keep outside. Though it may not look like much now, Flint castle held out against many sieges in its lifetime and gave it all she had, one must respect that.

Not far from the castle, on the top of Flint Mountain, is a magic pool called Pwll-y-Wrach, or, “The Witches’ Pool”. It is said that the ellyllon, supernatural beings, congregate at Pwll-y-Wrach after dark. These Welsh spirits are not to be trifled with, as this tale will show, and the Witches’ Pool is a place where humans would do well to stay clear of. On a cold winter’s morning in 1852, a labourer by the name of Thomas Roberts was setting out to work. After walking a while, Thomas passed nearby the ellyllon’s pool and was suddenly confronted by a small boy in his path. Roberts tried to get the boy, who was completely blocking the trail, to move aside, but the youth paid no attention to his questions. Getting frustrated, Roberts attempted to push the lad out of his way but the youth, with incredible strength, tossed Thomas across the field to land next to the Witches’ Pool. An invisible force pressed down on Thomas’ head and no matter how hard he struggled he could not move. Upon hearing a rooster crow the magical force suddenly released Thomas and he quickly jumped to his feet. The strange boy before him looked at Roberts impassively and then proclaimed a prophecy, “When the cuckoo sings its first note at Flint Mountain, I shall come again to fetch you.” Thomas Roberts died the following May, 1853. He had been carrying out some building repairs at the village of Penyglyn on the mountain when a wall fell and crushed him. A young woman, who had witnessed the accident, said that it happened just as she noted a cuckoo come to rest on a nearby tree. She added that when the body was being carried away to Roberts’s home, the cuckoo had followed, singing all the way to his front door. What’s interesting about this story is that within historical records there truly was a Thomas Roberts who died in 1853, crushed by a wall. Whether it was poor building or an evil goblin behind the cause of Thomas’ death can simply be left up to the imagination.

Before the invention of gunpowder, which marked a new era of war, there was no military power greater than a castle. With a castle, a few men could defend themselves against an army of thousands, and one man could claim lordship over a country. Those who owned the castle held the power, and wars upon wars were fought to gain that ownership, conflicts that cost the lives of so many in the name of their Kings. But, despite their terrible past, these ruins left behind from a darker age provide us with a glimpse into a different world. Today they provide evidence of a turbulent history, astound us with their feats of engineering and beauty of design, and stir our imaginations into tales of heroes, princesses, and ghosts. Our journey through the British Isles gave us the chance to explore these epic strongholds, something that cannot be found in our country, and we pushed ourselves to see as many as we could find in the areas we were staying; England, Scotland, Ireland, and finally Wales. After 16 castles I have to say that I’ve had enough for now, though I do not regret it. My only hope is that after reading this you will be inspired to visit them yourselves, and experience the awe as you stand in front of some of the greatest British castles.

Great trip; you saved the best for last; then again I’m biased as I grew up in Flint :o)