Out of all the wonders we’ve witnessed in our travels through Europe, our workaway experiences have been the most memorable. In Finland we lived with an alternative community, constructed a yurt and worked on a straw bale home. In Hungary we helped renovate a 200 year old adobe brick house. We walked dogs through the Balkan mountains, babysat 3 kids in Vienna, helped bring back a lost garden in Scotland, and made caramelized sugar schnapps in Poland. We built relationships with people across the continent through the opportunities provided by work exchange organizations. Workaway forced us to get off the beaten, tourist trail and experience what we would otherwise have ignored. Our 18th and final workaway experience, within our 22 month European journey, began on the island of Crete. It was in the seaside town of Stalida one evening where we met the hyperadobe earth building visionnaire, Michael.

It was already getting dark as we stepped off the bus on the outskirts of Stalida. We had traveled all the way from the other side of Crete to meet up with our workaway host at his construction site. Michael’s workaway profile said he needed volunteers to help realise his dream: an art and community centre built out of earth. At this point we had very little idea about what an earth house would look like, much less how to build one, but we were eager to find out.

Earth Construction

Earth construction has been around for thousands of years, since man first started creating their own dwellings. Early forms of earth building included baking mud blocks in the sun to make bricks. These adobe bricks, a mixture of dirt, clay and straw, are still used in most parts of Africa where timber resources are limited.

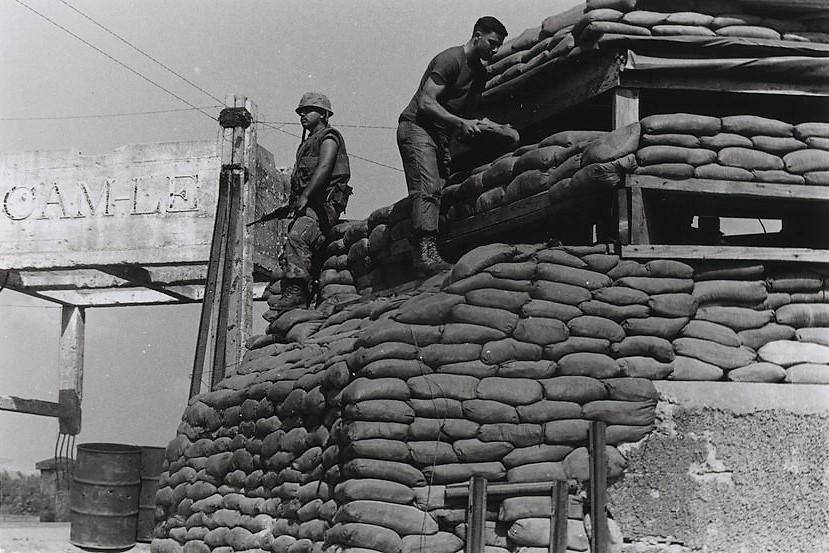

Earth construction evolved in military operations where they would use sand bags, filled with moistened dirt, to build temporary bunkers.

Borrowing from the military’s earth bag technique, Nader Khalili developed the superadobe design for NASA as a housing solution for possible future moon and mars colonies. I admit that does sound out-of-this-world, but Superadobe was later recognized as a more plausible solution for emergency shelters. The superadobe technique requires a significant amount of labour but uses dirt-cheap materials (pun intended) and can be built by unskilled workers. During an emergency situation where natural forces have wiped out a settlement, superadobe bags are light, making it cheap and easy to transport to an affected area. Survivors can then work together filling superadobe bags with dirt, using minimal tools, and build sturdy shelters to protect them from the elements.

Taking superadobe to the next level, Fernando Pacheco from Brazil invented Hyperadobe, an earth-building method our workaway host chose for his masterpiece.

Following the directions Michael gave us, we walked down a small lane into Stalida and miraculously found the building site. We couldn’t see much in the dim evening light except a wavy mud wall embedded with rubber tire portals. We tentatively walked through the gateway and called out a greeting into the shadows. A red-earth mud man emerged and gave us a vigorous handshake, introducing himself as Michael. Michael explained that we’d have to hitchhike up the mountain to the village of Mohos, where he lived. It was almost completely dark, had started to drizzle, and I had my doubts that we’d be able to flag down a willing driver. Michael, however, was perfectly optimistic and it wasn’t too long before a local Mohosian took pity on us.

Mohos

Although agriculture is still a major industry in Crete, tourism has become the primary source of income for its citizens. Passing through the main square of Mohos we could see what was once a farming village had transformed into a tourist attraction. The square was paved with brand new cobblestone and lined with brightly lit cafes and bars. Although the main plaza was basically empty, the restaurants were open for business as if expecting a wave of tourists to come up the mountain at any moment.

We continued following Michael through the dimly lit village of white-washed stone until we arrived at his home. I have to admit his house was the smallest I’ve ever seen, but Michael graciously offered his bedroom to us. He then showed us his rooftop terrace revealing lovely views of Mohos and the surrounding hills. Later that evening we returned to the main square of Mohos where Michael treated us with a traditional Cretan Meze along with a few shots of Rakia (plum brandy). The meze included fruit, stuffed olives, broad beans, snails and other appetizers. It was the first time I’ve ever tried snails and although I couldn’t get used to the slimy texture it wasn’t half bad. Michael talked to us about the work we would be doing in Stalida the next day and we were excited to learn about the hyperadobe process firsthand. After finishing our exotic meal, we sipped Rakia and soaked up the quiet, contented atmosphere of the village square before turning in for the night.

Michael’s Hyperadobe Home

The next morning we were back on the road hitchhiking to Stalida. We hopped in the back of a pickup truck and enjoyed the marvelous view of the coast while we were driven down the mountain. In the daylight we could clearly see Michael’s building site and the work that needed to be done. Tragically, a week of heavy rainstorm had destroyed most of the building before they could put a protective layer of plaster on it. A earthwall surrounded the property and parts of the original building still stood, but the once magnificent dome roof had collapsed. I don’t know if I would have the will to continue my project after such a catastrophe, but Michael would not let himself give up.

We could tell how much Michael appreciated the artistic side of things. The site was decorated with art pieces made from shells and reclaimed, coloured glass. Flowers were planted everywhere, including strawberry and pepper plants. He even got Ashleigh working on a snail mural before we started building anything.

Exploring Crete

Michael was such an easy-going guy that we were sorry in the end because we felt like we could have helped more. Every day we would hitchhike down the mountain with Michael and he would either teach us about hyperadobe, we’d work together on an art piece, do some plastering, or just relax on the beach of Stalida drinking frappés. By the way, a cheap but effective home-made frappé coffee: water bottle, instant coffee, sugar, shake shake shake and voila! Sometimes Michael’s zen friend, Versailles the Goldsmith, would show up at the worksite and give us pointers.

Michael would often change his mind about what we were doing that day, or sometimes call the whole day off and postpone until tomorrow, so we had a lot of time for tourism. On our days off we hiked through olive groves to nearby villages such as Hersonissos and Archanes, including the flooded village of Sfendily! Michael gave us a home base in Crete for touring, but on the days we would work he always kept it fun and interesting.

The Basics of Hyperadobe

The only major difference between hyperadobe and superadobe is that hyperadobe uses knit raschel bags instead of polypropylene bags. With hyperadobe, you don’t need to lay down barbed wire between the layers to tie them together as you do with superadobe. The open netting in hyperadobe allows the layers of earth to merge together with some added water.

The best soil to use for hyperadobe should be a mix of 30% clay and 70% sand. We used an open bottom bucket to help us with the process of laying down the earth layers. We started by scrunching up a long tube of the raschel bag onto the bucket and tying off one end. While one person held the bucket, shaking it and slowly moving down the line, another person filled the bags with earth through the bucket. Kind of like squeezing out a line of tooth paste, the first layer of the earth wall is put down and then tamped with a flat, heavy object. Before adding a second layer of earth you must wet the first layer so they can meld together. That’s pretty much it for a simple wall, as long as you remember to tamp and wet each layer the wall should be very sturdy.

Rain will eventually disintegrate the hyperadobe wall, so to protect it, you must cover the earth with a layer of plaster. Michael showed us how to mix our own plaster with clay, sand, cement. lime and straw. We mixed all our materials in a tarp by frolicking around in it for ten minutes and then applied it to the walls by hand. The lime is caustic, however, so you should remember to wear some protective footwear and gloves.

Our Final Workaway

Without work exchange programs like WWOOF, Workaway, and Helpx, I believe that our Europe trip wouldn’t have felt as satisfying. It’s exciting to tour around and explore beautiful places, but without some kind of human connection it’s only a thrill-ride. Ashleigh and I are both introverts but Workaway brought us out of our comfort zones. Workaway forced us to live and work with people from all walks of life, and though it may not have been all perfect, it gave us a stronger connection the places we were visiting. On top of that, Workaway helped us save a lot of money on hotels and eating out. Thanks to our hosts, we learned more about the culture we were in and discovered places we couldn’t read about in a travel guide.

We were sad we couldn’t have stayed with Michael long enough to see his hyperadobe building to completion. We hope with all of our hearts that one day he will realise his dream.

Hi,

I’m considering to build a super/hyper adobe here in Crete as well, would appreciate if you could contact me with Michael,

I would love to understand how he got a permit for building.

Hi Galia, we’ll see if we can dig up his contact information for you.

Hello Nathaniel,

Great article and amazing experience. Did you recover the contact details of Michael? Best, Rodrigo

Hello Galia, did you end up building something? We have the same idea, and would like to know about your experience. You can write me at [email protected]

Hi , great project!

I am looking for the raschel hyperadobe tube, do you know where we can order this In Europe?

We live in the Netherlands.

Thanks

Hi!

I would also love to contact Michael about earth building in Crete. Did you manage to dig up his contact?

Thank you!