Tourists visit Greece to explore archaeological wonders like the Acropolis, but they often forget where western civilization truly began: in Minoan Crete. Home to the Minoans long before Athen’s heyday, the kingdom of Crete boasted magnificent palaces, cities, and a rich culture that influenced most of the Mediterranean. Although it is shrouded in mystery and legend, archaeological evidence gives us a glimpse into the rise and fall of this advanced society. During our travels through Crete I made it my mission to visit these ancient Minoan sites and examine the evidence of their greatness firsthand.

Theseus and the Minotaur

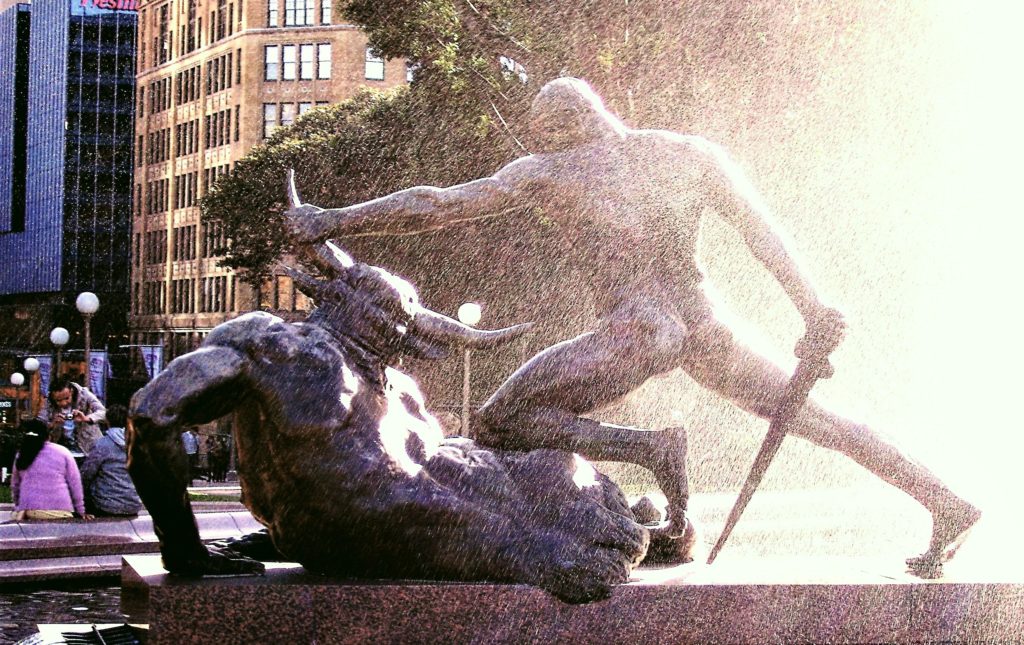

Many of us have heard the most popular story of Crete: Theseus and the Minotaur. King Minos of Crete held dominance over the Athenians at the time of the tale. As tribute, Minos demanded seven young men and seven young women from Athens every year. These prisoners would be sacrificed to a monstrous, humanoid bull living in the labyrinth beneath Minos’ palace. On the third year of tribute, a hero named Theseus finds a way to defeat the minotaur. Using a ball of twine, Theseus marks his trail into the depths of the labyrinth. The hero confronts the dreadful monster and slays it in battle, thus temporarily ending King Minos‘ reign of terror.

Minoan History and Culture

The tale of the Minotaur is the only written “history” we have left about the Minoans. The story was constructed by the Ancient Greeks about their enemies, the Cretians, so it’s difficult to say how much of it is true. Archaeological discoveries in Crete, however, have shed light on the Minoan people and have even made connections to the legend of the Minotaur.

The Minoans flourished in Crete and the islands of Greece between 2000-1470 BC. In the Odyssey, Homer states that Crete once had a large population with 90 cities. The Minoans built magnificent palace/religious centres so intricate they were like labyrinths. Excavations of these palaces have revealed frescoes and sculptures depicting bulls and themes of nature. At Knossos, a restored fresco portrays young men and women leaping over charging bulls. With the vast amount of bull images found at Minoan sites, we can conclude that they either worshiped the bull or held it sacred. Even if the story of the Minotaur isn’t true, it was certainly inspired by Minoan culture.

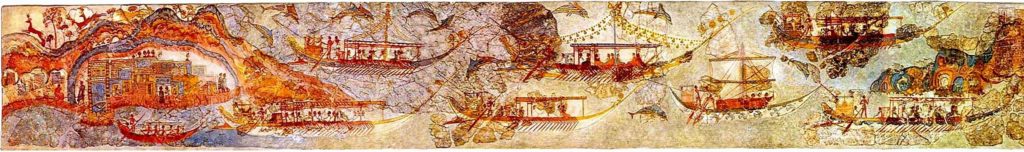

At their height the Minoans dominated the Aegean Sea and had a sophisticated culture on par with the Ancient Egyptians. The Minoans traded all around the Mediterranean, from Spain to Israel. Their trade routes influenced cultures from what was considered to be the centre of human civilization. Minoans had their own style of art and sculpture as well as their own written language which, unfortunately, is still indecipherable today.

Minoa remained a powerful force in the Mediterranean until, around 1500 BC, a cataclysm weakened them to the point of no return. Archaeological evidence attributes Minoa’s decline to the eruption of Thera, one of the largest volcanic events in known history. Subsequent earthquakes and tsunamis devastated Minoa allowing the rising Mycenaeans to swoop in and take command of the Aegean. The Mycenaeans evolved under the influence of Minoan Crete and founded many of the grand cities of Ancient Greece, like Athens and Thebes. Therefore, our notions of modern, western society stemming from Ancient Greece should instead be accredited to the Minoans.

Minoan Palaces

The capital city of Knossos was the first major Minoan archaeological site. Before the discovery of Knossos in 1878 (by Minos Kalokairinos), the Minoan civilization was virtually unknown. It was Arthur Evans who went to work uncovering and restoring Knossos to the best of his ability. One of the driving forces behind this excavation was the theory that Knossos was the mythical labyrinth of King Minos. Unfortunately, archaeological practices in the 20th century were reckless compared to modern standards and some of the “restorations” aren’t entirely accurate. Still, Evans’ rebuild of Knossos brought interest to the Minoans and inspired further excavations. The site of Knossos also jump-started tourism in Crete; everyone wanted to walk the labyrinth that Theseus once braved in days of yore.

What drew me to Crete was of course the story of Theseus and the Minotaur. Bringing truth and life to mythology is always exciting for me, which is why we visited sites like Troy (The Illiad), Glastonbury (King Arthur), Dundalk (Cúchulainn), and Rome (Romulus and Remus). Visiting the site of Knossos was an exceptional experience. Unlike most archaeological sites, much of Knossos has been restored, thanks to Arthur Evans, so you can get a clear depictions of Minoan art and architecture.

Knossos

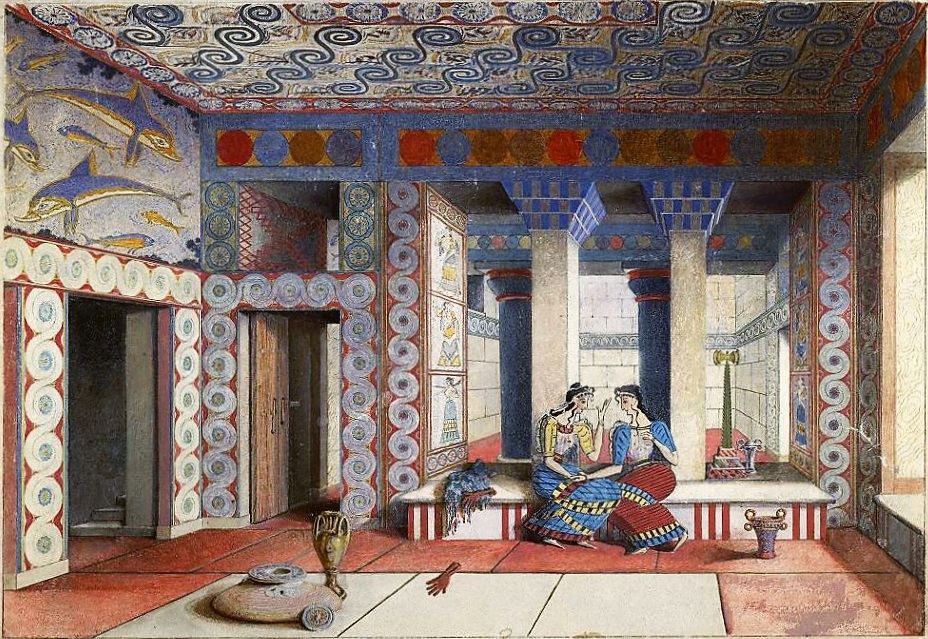

In its heyday, Knossos was the religious and political centre of Minoa. It was not just a residence for the royal family but a plethora of markets, workshops, and religious spaces. At its peak, around 1700 BC, the palace and surrounding city of Knossos held 100 000 people. The architecture of Knossos was very advanced for its time; some buildings reached as high as five stories. The palace complex had a confusing layout lacking any symmetry, with multiple levels and various sized chambers. In the middle of this labyrinthine layout was a massive central court used for performances or religious ceremonies.

In its heyday, Knossos was the religious and political centre of Minoa. It was not just a residence for the royal family but a plethora of markets, workshops, and religious spaces. At its peak, around 1700 BC, the palace and surrounding city of Knossos held 100 000 people. The architecture of Knossos was very advanced for its time; some buildings reached as high as five stories. The palace complex had a confusing layout lacking any symmetry, with multiple levels and various sized chambers. In the middle of this labyrinthine layout was a massive central court used for performances or religious ceremonies.

It was a beautiful day and we enjoyed walking through the many levels of the palace complex. We could see from the restorations that Minoans loved the beauty and colour of nature and decorated their homes this way. I tried to imagine King Minos sacrificing Athenians to a monstrous bull in this beautiful palace and just couldn’t believe it.

Malia

Although Knossos was the capital city in ancient Crete there were many other palace complexes on the island. About 40 kilometres east of Knossos, built nearly 4000 years ago, is the palace of Malia. It was the third largest Minoan palace, with similar architecture to Knossos, right on the delightful, Cretian coast. According to legend, King Minos’ brother, Sarpedon, ruled Malia. Much like Knossos, Malia was both a royal palace and administrative/business centre. The palace contained religious sanctuaries, workshops, storage magazines and a theatre. All Minoan citizens were allowed into the palace to shop, lounge, pray, and be entertained.

On one of our days off from earth building in Stalida we decided to take a long walk to the ruins of Malia. It was a grueling, 13 km walk in the hot sun, but we managed to get there without blacking out. Malia hasn’t been reconstructed to the extent of Knossos, so it may lose the interest of mainstream tourists. The foundation walls give you a skeleton of the palace’s layout but your imagination must do most of the work. I still thoroughly enjoyed it, running through the rooms and passageways like a kid in a corn maze (I even got yelled at by a security guard).

The Minoan people were incredibly sophisticated for their time, ruled the known world, and laid the foundation for western society. While the Ancient Egyptians were living in mud huts and slaving away to build pyramids for the dead, the Minoans were living in luxurious palace complexes. Through their artwork and archaeological evidence you can see how the Minoans celebrated life and nature. Maybe they lived too well, for like Atlantis, the gods grew jealous of their prosperity and brought the Minoan civilization to its knees.